Farms and farming come in all different shapes and sizes – from buffaloes to bantams and worms. Each farm has its own unique requirements and environmental conditions to consider if quality products are to be produced in the most efficient and effective manner. The 4th Industrial revolution has helped farmers manage their farms in a variety of ways including using remote sensing and the Things Gateway Network to collect, aggregate and analyse real-time data to inform farm management decisions.

Introduction ...

I’m a farmer, of sorts. I currently have herds in the order of hundreds and thousands. My aspiration is to have herds in the millions! Fortunately for me, they’re micro-herds; herds of small critters. To be more specific, I farm flies – lots of them!

Hermetia Illucens – more commonly known as the Black Soldier Fly is a marvel of nature. Unlike common houseflies, the Black Soldier Fly is non-invasive and not a vector for many common pathogens. They have a relatively short lifecycle and an adult female can lay clusters of up to 500 eggs. But why would you want to farm flies?! Well, not so much the fly but the immature version of the fly, the Black Soldier Fly Larvae.

The larvae are voracious consumers of organic materials and efficiently convert this to body mass that typically consists of up to 40% protein, 12-28% fat and 8% minerals. The larvae are being readily considered as an alternative protein source for the livestock and aquaculture feed sectors. Pharmaceutical and industrial chemical companies are also interested in oils and components of the black soldier fly (and larvae), including chitin.

Our farming operation ...

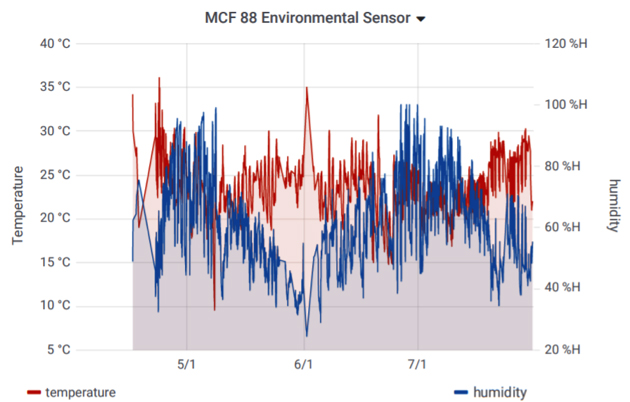

The Black Soldier Fly originated in South America and central Americas. It breeds most effectively in warm, humid conditions: 24-40 degrees Celcius and 70% humidity. My farm is located in Adelaide, South Australia; approximately 3,880 kms south of the Equator. It is not possible to farm the black soldier fly in ambient environmental conditions here all year round due to our cold winters and hot, dry summers. Hence, artificial heating, cooling and humidification is necessary to provide optimal breeding and egg hatching conditions.

In February 2019, we introduced our first batch of black soldier fly larvae to our purpose built pilot facility. Temperature was crudely controlled by an on/off thermostat on the electric heater. Similarly, a bench-top humidifier operated during the warmer months to increase the humidity. In March 2019, we installed a MCF-LW12TERWP-AU LoRaWan outdoor environmental sensor with associated receiver and transmitter connected to the Things Gateway Network. This has enabled us to remotely monitor the temperature and humidity within the insectarium. In June 2019, a reverse-cycle air conditioning unit was installed to replace the domestic electric heater.

The figure below shows the temperature and humidity traces covering the period April – August 2019.

The data has been beneficial for several reasons:

- Monitoring of ambient and controlled room conditions across different seasons

- Influence of heat generation by the larvae as they grow on the room temperature and humidity

- The efficacy of the reverse-cycle air conditioner in responding to changing conditions (particularly over winter and across various larvae life cycles)

As we continue to further refine our processes and validate our environmental boundaries for optimal fly breeding and larval production, data such as that collected by the LoRaWan outdoor environmental sensor will become increasingly important.